On June 8-9, Kathy Sullivan and Vanessa O’Brien became the first women to reach the deepest known point in the ocean, the Mariana Trench. Neither are new to world firsts: Sullivan, 68, is an astronaut and oceanographer; she was the first American woman to walk in space in 1984, and later became the administrator of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). O’Brien, 55, is an accomplished mountaineer and became the first American woman to summit K2 in 2017.

Limiting Factor on a previous dive.

Previously, only three dives have successfully reached the Trench, 10,984m below the surface of the Pacific Ocean. Don Walsh and Jacques Piccard made it to 10,916m as part of a Navy exercise in 1960. In 2012, Titanic director James Cameron reached 10,908m during a solo dive, and in 2019 Victor Vescovo set the world depth record after diving to 10,925m in his submersible, Limiting Factor. Rather than a sphere or a cylindrical submarine, it’s been said to resemble “a squashed milk carton”.

Vescovo, in partnership with the NOAA, organized the latest expedition, with Sullivan and O’Brien doing alternating dives in the same two-person submersible, with Vescovo piloting both times. Their aim was to map and collect samples from the depths of the Mariana Trench.

O’Brien emerges from Limiting Factor after 11 hours in the Mariana Trench. Photo: Enrique Alvarez

ExplorersWeb spoke to O’Brien about her 10km descent into the depths of the Pacific.

You are primarily a climber. How did you get involved in this project?

My participation has its roots in climbing. I met Victor in 2013, when the past chairman of the New York section of the American Alpine Club decided to award seven summit certificates, and Victor and I were on his list. Ironically, this was the first and last time this type of “seven summits” event ever took place, but it was a catalyst for me to meet Victor. We both went on to ski the last degree to the North and South Poles. Then I continued climbing five 8,000m peaks and Victor went on to dive the five deeps.

What drew me to the project was that I saw oceans as an extension of mountains, a bit like how Mauna Kea is said to be taller than Everest, if one measured a mountain starting at its base, which for Mauna Kea is under water. I also believe both extremes have similarities: high altitude and deep depths both contain risk, occur in the dark, are challenged by oxygen, involve cold, have a “summit” moment and require intense concentration.

O’Brien and Victor Vescovo in Limiting Factor. Photo: Enrique Alvarez

What is it like down there?

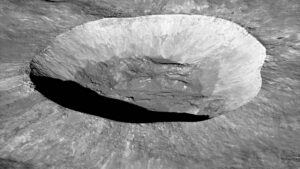

Challenger Deep (the deepest known point of the world’s oceans) was very dark, but we did have lights, so we could see through one of three portholes. At first glance, the bottom appears to be just fine sand, but in reality it is probably sediment from the oceanic plate colliding into the continental plate. There is very little current, almost none at all, and if you looked closely, you can just make out a few tiny things slowly moving underneath the sediment — most likely bristle worms or other hadal zone creatures.

The bottom of Challenger Deep. Photo: Vanessa O’Brien

Do your ears pop when you go down seven miles?

Your ears are safe, the same way they would be in a pressurized cabin on an airplane. However, unlike an airplane, the submersible creaks and cracks every now and then — your imagination runs away with you.

How does seven miles down differ from three miles down?

Frankly, both are dark, and if you were hovering in one vs the other, you probably wouldn’t know the difference. The biggest changes would be the different pressure and species. The ocean is split into five layers from top to bottom, and 1,000m falls on the edge of Zones 2 and 3. In the deeper Zone 3, larger sea species like sperm whales are found, and the pressure can reach 5,800 psi. By the time you hit the deepest Zone 5 at the bottom, you reach 16,000 psi.

A polychaete, a kind of marine worm, at Challenger Deep. Photo: Victor Vescovo

How long does it take to descend/ascend?

It took four hours to descend and four hours to ascend. We were able to spend three hours completing our transect along the bottom, as part of the survey team in the eastern pool. We were able to reach 10,925m.

What were your favorite and least favorite parts of the dive?

My favorite was the first time I climbed into the submersible. It was surreal when the hatch opened and I had to figure out how to get in by lowering my legs one at a time on to the hand holds. I honestly didn’t think I would get my shoulders through. Suddenly you are seated in what looks like something reminiscent of I Dream of Jeannie or Barbarella.

My least favorite was finding our starboard batteries drained of power. It reminded me of that phrase… what is it again? Oh yeah… electricity and water don’t mix. That probably accounts for the number of electricians on board, too!

Were you scared at any point?

Only when we jumped from the ship into the water. It was a much longer way down than I had anticipated, and I seemed to be suspended in the air a bit too long. Let’s just say mountaineers don’t like to free fall, it means something’s wrong. All descents should be controlled.

However, when the starboard batteries flashed red…nah. No fear there. That meant time for troubleshooting. Can we borrow power from the port side? Can we turn 180 degrees and use port power to complete the transect on the starboard side? The way I look at it, the five rosaries in my pocket…were the best insurance policy for any of that serious stuff.

Fear happens when you are not in control. At no time were Victor or I not in control. He was, after all, the first man to reach Earth’s highest and lowest points. After this dive, I would become the first woman to reach Earth’s highest and lowest points. And to think we met at an American Alpine Club event collecting Seven Summit certificates seven years earlier. Who would have suspected it then?

One giant leap: Vanessa O’Brien (black) and Kathy Sullivan. Photo: Enrique Alvarez

What are the biggest dangers on an expedition like this, and what were the safety measures in place?

Well, stating the obvious, I suppose the biggest danger would be something going wrong in the submersible! There was a fairly famous incident with Hybrid Remotely Controlled Vehicle (HROV) called Nereus that was lost while exploring the Kermadec Trench at 9,906m. After communications was cut off, debris was found, and it revealed pretty clearly that the submersible had imploded due to high pressure. One can never forget the 16,000 psi or 292 jumbo jets of pressure pushing down on the submersible is the biggest risk.

Of the two previous manned submersible dives in 1960 and 2012, both vehicles were retired after a single dive. This is why Limiting Factor has a 90mm thick titanium pressure hull. It has plenty of redundancy, including emergency systems such as temporary and emergency oxygen systems and weights that can be released for added buoyancy to the surface.

How much of the diving and sampling did you carry out? Is this all automatic or controlled by teams up on the surface, or have you had to train to use all of this equipment?

Together, Victor and I formed one submersible team, taking one transect along the eastern pool of the Mariana Trench. Victor is always the pilot, but the submersible survey partner changes. We are taking photographic evidence, operating the robotic arm and generally double-checking the stats that Victor calls out or writes down.

On my dive, we were able to observe a six-metre slope over about a mile. The robotic training was one day only, but it is harder than it sounds because you are trying to operate something remotely, with limited vision, and against water pressure and currents.

Challenger Deep is named after HMS Challenger, the ship that first discovered this area as potentially the deepest point. HMS Challenger was a Royal Navy ship that was refitted to undertake the first global marine research expedition between 1873-1876. The Natural History Museum in London received many of those original collections, including water samples dating back 150 years. That gave me the initial idea to reach out to them and make a donation to the museum; the water we collected was sampled at 10,916m.

O’Brien collected water samples for the Natural History Museum in London. They are kept in a freezer at -81C. Photo: Durdana Ansari

As one of the aims is to map the deepest pool of the Mariana Trench, the Eastern pool, will you have to carry out multiple dives to complete this?

Yes, there will be multiple dives of the Eastern pool, to re-check previous data from last year, and to provide more definitive data in partnership with NOAA and to send to GEBCO to help meet their target for mapping all the oceans by 2030. We used a Kongsberg EM 124 Multibeam echo sounder, which is the top-of-the-line kit for high-resolution data at up to 11,000m.

Multi-beam sounders measure the speed of sound as it travels to and from the bottom of the sea floor. Once the data is adjusted, ultimately, we would like to show a 3-D image of what the seabed looks like. Is the Mariana Trench a billiard table or does it contain hills and valleys? Eighty percent of our planet’s oceans have not been mapped. We know more about the surface of the moon and Mars!

Have you read any books about this sort of thing— 20,000 Leagues, etc. — that made you smile at their inaccuracies or marvel at their prescience?

No… but there were plenty of people talking about a film called Underwater, starring Kristen Stewart, that takes place six miles deep, something about a big sea creature — I’m pretty sure it is a horror flick! Maybe there are some scenes I can splice into my footage for a “mock” dive –- that’ll be fun!

How does it feel to be one of the first two women ever to experience this?

It is really amazing, and I am grateful for the experience. It has been fun and challenging to learn about mapping, submersibles, oceans, hadal zones and the history of HMS Challenger. I have enjoyed working with all the members of the team, from the captain and crew, the chef and his team, the submersible team, the mapping team, Victor as the organizer and pilot and everyone who came together to donate their time, talent and treasure to make this a success.

Pre-Dive mapping meeting (Vanessa O’Brien and Victor Vescovo, centre facing). Photo: Durdana Ansari